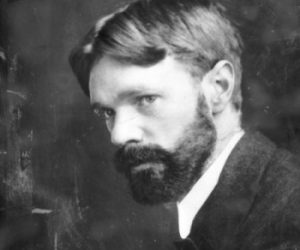

Portrait of a Genius, But…

Richard Aldington

Published by Heinemann (1950)

Of all human beings I have known he was by far the most continuously and vividly alive and receptive. (Richard Aldington, writing of D.H. Lawrence in Life for Life’s Sake, 1941)

A man so strange and inspired that he seemed to live in a finer, more luminous world than other men. (Richard Aldington to Alexander Frere of Heinemann, 12 January 1935)

I suppose you and I know as well as anyone living how disagreeable and offensive DHL could be, but by God when I go over the evidence and see how those people tried to crush him by any foul trick I do feel on his side. And after all on the great (?) side we shall never know anyone like him, shall we? (Richard Aldington to Martin Secker, 6 March 1949)

D.H. Lawrence died from tuberculosis in 1930 at the age of forty-four. In May 1941, Aldington, with his wife and daughter, spent two months at Lawrence’s beloved New Mexico ranch, now the home of his widow, Frieda, and her partner, Angelo Ravagli. He wrote:

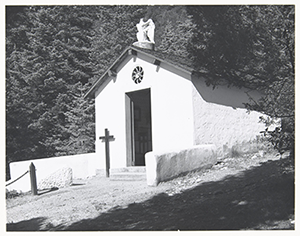

Few remember better than I that mysterious gift Lawrence possessed of making life around him seem exciting and wonderful, as if in his world the very air were not common air but pure oxygen, where everything glowed and vibrated with more intense colour and vivacity. Up here I am constantly reminded of him – the bed I sleep in he made, on the rough stone seat by the hearth still lies the little rope mat he wove; the first thing I see from the porch in the morning is the great pine he loved so much, and from everywhere you catch glimpses of that intensely silent and peaceful little chaple [sic].

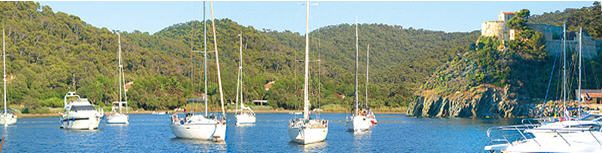

I come out of my New Mexican shack and look about me. There in the sunlight stands so quietly the grave of the English poet, with above it the white phoenix which he chose as his emblem … Strange resting place, if indeed it is the last resting place, for the ashes of the ‘common’ Derbyshire coal-miner’s son, ashes which seem to share the restless wanderlust of the living man, having already journeyed so many thousand miles over sea and land. Strange but most fortunate among the many literary exiles of England who lie buried in other lands. I think of the graves of Landor and Elizabeth Browning in what is now a dullish Florentine suburb, of Keats and Shelly [sic] in the little Roman cemetery, of Fielding in Lisbon. They cannot compare with the serenity and majesty of Lawrence’s burial place, where the extreme simplicity of the grave is so right. …

In 1949, at the request of Heinemann and the Penguin director Allan Lane, Aldington set about writing a biography of Lawrence and introductions to the Lawrence works that were to appear in both publishers’ imprints to mark the twentieth anniversary of Lawrence’s death. Portrait of a Genius, But … was not Aldington’s first attempt to perpetuate the reputation of his friend. His first monograph on Lawrence had been written in 1927, and from 1932 onwards he had edited several of the works He told the D.H. Lawrence scholar Edward Nehls in August 1956: If my life has any value, it is that since 1926 – and to some extent since 1914 – I felt his superiority and always acknowledged it.

The biography is written from the perspective of a close friend and unswerving admirer but one with a clear-eyed awareness of the complexities and drawbacks of Lawrence’s remarkable personality. Aldington is also a discerning literary critic with a thorough familiarity with the totality of Lawrence’s output.

The biography is written from the perspective of a close friend and unswerving admirer but one with a clear-eyed awareness of the complexities and drawbacks of Lawrence’s remarkable personality. Aldington is also a discerning literary critic with a thorough familiarity with the totality of Lawrence’s output.

The result is a measured, searching but also profoundly touching portrait. Aldington’s own battles over the censorship of Death of a Hero and All Men Are Enemies and the refusal of the libraries to stock The Colonel’s Daughter made him deeply sympathetic to his friend’s sufferings over the banning of The Rainbow in 1915 and the reception of both Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Lawrence’s paintings in 1928 and 1929.

His own resentment of the literary establishment was intensified by his consciousness of its failure to acknowledge Lawrence’s genius or to come to his support during these crises.

It also took a writer who had himself grown up in a dysfunctional family to recognise how profoundly Lawrence’s irascible nature was formed by his early training and environment. It is more remarkable that, despite his accustomed resentment of fellow writers who had not served in the Great War, he produced a moving account of Lawrence’s persecution at the hands of the authorities in Cornwall in 1917.

Writing in the Times Literary Supplement, Malcolm Muggeridge called the book an admirable biography, honest in intentions, affectionate in spirit and generous in appreciation.