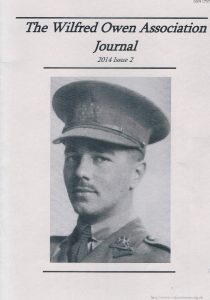

Vivien is a member of several of the member societies of the ALS, and we are delighted to have the opportunity of reviewing a book which must certainly be of interest to many of our readers, particularly at this moment when the First World War is so prominent in our minds. It is 25 years since the last major biography of Aldington, although collections of letters from and to him have been published, but this biography of the most important part of his development will be most welcome to anyone with an interest in the literature of the period. Richard Aldington was what people today call ‘connected’, so even if you don’t already know and admire his work you will be interested in his relationships with D H Lawrence, TS Eliot, Ezra Pound, Ford Madox Ford, Wyndham Lewis, Herbert Read and many more. Through this book you can begin to know his work, his poetry and novels, although the book ends with the publication of Death of a Hero in 1929.

This is an absorbing and thorough discussion of Aldington’s life and work, and illuminates the cultural life of London throughout the period. In three sections, dealing with the periods before, during and after the First World War, it vividly recreates the networks of relationships, the scandals and passions of Aldington’s life, his marriage to Hilda Doolittle (HD) the American poet, his various lovers, but above all his life in writing. The research is thorough and presented with a remarkably light touch, considering the level of detail here. Vivien Whelpton is to be congratulated on a very substantial achievement in a book which will long resonate with its readers.

Deb Fisher

~~~

The Use of English

The Use of English

(The English Association Journal for Teachers of English)

Vol. 65, No. 3, Summer 2014, pp. 98-100

… To describe Aldington as a complicated individual is an understatement, and to call his relationships with other people complex is equally inadequate. It is one of the strengths of Vivien Whelpton’s biography that she examines these complexities with great patience, clarity and objectivity. She does not hesitate to show how capable Aldington was of causing offence, bewilderment and grief, nor does she scruple to convict him at different times of self-pity and of heartlessness, but she also makes clear that he was a man with a great capacity for friendship and loyalty, and for inspiring these qualities in those to whom he was close.

His relationships fall into two categories: relationships with other writers – most importantly with Ezra Pound, with T.S. Eliot and with D.H. Lawrence – and relationships with many women, above all with the American poet, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) his lifelong friend and, briefly but ineluctably, his wife. Part of his importance lies in the fact that, despite being so closely involved with the key developments in English literary modernism from Imagism onwards, he became the modernist who turned his back on modernism. After all, before he joined the army in 1915 he was a key contributor to The Egoist, and after the War he was for a time Eliot’s assistant editor of The Criterion – not a bad CV for someone who was still only 26 when the war ended.

Vivien Whelpton naturally gives a detailed picture of Aldington’s experience as a soldier: in training in Dorset, at the Front and in London on leave. She makes full use of his letters, particularly to H.D. and to his fellow Imagist F.S. Flint, to record his developing revulsion against army life and his experience of trench warfare. But it is from Death of a Hero that she is able to mine the most telling details of his response to the war. Indeed, it is striking that Whelpton’s portrait of Aldington is able to draw so heavily on a range of romans à clef written by his friends and by himself. There can be few writers who have featured so frequently in the lightly-veiled fiction of his friends – and occasionally of his enemies: Miranda Masters, by John Cournos, Bid Me to Live and Asphodel by H.D., Aaron’s Rod by D.H. Lawrence and The Colonel’s Daughter and the revealingly entitled All Men are Enemies by Aldington himself. Whelpton is scrupulous in distinguishing between documented fact and fictionalized reconstruction and hypothesis, both in the illuminating endnotes to each chapter and in the body of the text itself. Her account of Aldington’s life in France, especially in the latter stages of the war from the time of the 1918 German Spring Offensive onwards, is graphically told and carefully interwoven with the story of his increasingly fragile relationship with H.D – a fragility tested to the point of collapse by infidelity and by the stillbirth of their first child.

The most moving and original chapters deal with Aldington’s life after the War, a period in which he tried to re-establish his career, not this time just as a poet and theorist of the by now passé Imagism, but as a critic and translator. Aldington’s importance as a promoter of French literature is easy to overlook, but this would be a mistake: he took seriously his work as reviewer of French literature for the TLS, and his championing of the work of Remy de Gourmont showed that he was more alive to the main currents of European writing and criticism than almost anyone else then in England.

It may well be that, today, Aldington’s most important writing is the body of work he produced – poetry, short stories and fiction – between 1920 and 1929. It is a lazy critical cliché to suggest it took ten years for the writers who survived to refine their wartime experiences into art. Vivien Whelpton does not make this mistake, and she is right to observe that ‘what distinguishes Aldington’s poetry from that of Blunden, Sassoon or [Herbert] Read is the absence of any nostalgia for the war’. In illustrating this, she highlights the significance of his poem ‘Eumenides’ (from Exile, 1923) and shows how it points the way forwards to his long poem A Fool i’The Forest (1925). Her reading of this now almost entirely neglected poem is exemplary and shows how inadequate and incomplete are most critical accounts of post-First World War literary history.

To read this book is to be convinced that Aldington still deserves an important place in the history of English writing in the first half of the twentieth century. Vivien Whelpton has thus written a challenging book about an author most publishers still prefer to ignore, and Lutterworth Press is to be congratulated for publishing it.

Adrian Barlow

~~~

New Canterbury Literary Society Newsletter

Vol. 42, No. 4 (Winter 2014) and Vol. 43, No. 1 (Spring 2015)

Twenty-five years after Charles Doyle’s previous biography, Vivien Whelpton’s compendious new life of Richard Aldington covers the most important phase of his career, from aspiring poet to successful novelist via his military service. Whelpton’s impressive research for Richard Aldington: Poet, Soldier and Lover, 1911–1929 draws on and makes available in print for the first time a vast array of archival material, as well as making use of the myriad romàns a clé by the Imagist circle and their many acquaintances.

… Whelpton posits that Aldington’s military experiences and their subsequent impact have been neglected by previous biographers, and works to address this. … He was physically and mentally affected by the war during it, immediately after it, and also long after the explosions of the subsequent global conflict faded. Whelpton addresses this well, and it will surely be a key aspect of her projected volume on the latter part of Aldington’s life.

… Whelpton’s account is formidably thorough, and a valuable addition to the biographical resources previously available to the Aldington scholar; it will also be useful to students of the First World War, modernist literature, and the early twentieth century. …

Opening of Andrew Frayn’s review

To read the full review in PDF format, please click here

~~~

Reviews in PDF format